Source

Media campaign for climate justice Compilation of monographs from the 2014-15 media project of Pipal Tree

For a while now, I have been doing some research on what forms food habits; the diversity of our palate and the health and nutrition we get from what we eat. This research was not particularly inspired by any great thinking. Rather, prompted by some conversations on whether or not we could be doing something else to lead healthier lives.

During the course of this ‘research’, I have been seeking answers to some very fundamental questions. Questions such as: Where does our food come from and does it provide us with the nutrition we need?

During the course of this ‘research’, I have been seeking answers to some very fundamental questions. Questions such as: Where does our food come from and does it provide us with the nutrition we need?Is there a reason we eat what we eat? We have always heard that there is a connection between where we live and what we eat…what is that connection? For example (and though I never preferred it), is there a reason why rice is so preferred in the South and deriving some insights from conversations with my grandparents over meals that we had shared, the question as to whether we had always eaten this way?

Why do our grandmothers keep telling us that the foods they used to make were very different from the foods that we eat now?

The quest for answers to these questions introduced me to some very interesting literature, subsequently leading to some very interesting discussions on why we cook whatever it is that we cook; about farming practices, and some thoughts on what I need to be doing differently on my part, both to provide for the nutritional needs of my family and to play a more responsible role as a consumer.

Though not really ‘intended’, what also hit me like a ton of bricks during the course of this research are the following:

1. The undeniable connection between our food habits and the delicate checks and balances of our planet – one of them the impact of farming practices and food habits on climate change.

2. The need to harness the intelligence of (mostly lost) local communities that have been suppressed over time in the name of ‘development’ to give way to the half-baked knowledge that most of us possess.

3. The fundamental realization that the knowledge we possess is but a product of systematic advertising by big corporations; linear thinking as a product of a far-removed-from-reality, school education that most of us have undergone; and a lot of lethargy on our part resulting from a certain self-obsession to focus on ‘just’ our busy lives leading to always adopting what’s convenient, rather than what’s right.

This is what I am going to be attempting to explain now. Let me start with the food that we are most familiar with and which we think provide us with all the nutritional needs that weneed…Rice.

Rice has been systematically monopolized through a push for policy and economic gains not for the health of the masses and certainly not for the health of the planet. It takes 3000 liters of water to cultivate 1 kg of rice, which amounts to 6 million liters of water per acre of rice cultivation.

With the erratic availability of water for agriculture as a result of changing patterns in our climate, rice farming would probably be the first to face the brunt, as it cannot survive acute water deprivation. So, if this is the food we are accustomed to, and over which we hold deep-rooted belief patterns, convincing ourselves that they solely provide for our nutritional needs, what will we do when rice farming is no longer feasible?

What seems to have saved the day for some farmers is the adoption of bio-diverse farming practices.

Monoculture farming of ‘cash crops’ has led to the inevitability of often hearing in the news: Dependence on one crop, rising debts, and eventual suicide.

Here is what we do not hear about and do not know about:

1) the systematic loss of soil fertility.

2) The lure of immediate gains of growing cash crops including more returns for the sale of cash crops in the local Mandi (market) which incentivizes farmers to grow them in the first place.

3) The push for the heavy adoption of chemical fertilizers by corporations to keep the soil ‘producing’ which farmers who do not adopt bio diverse farming practices become heavily dependent on.

Kumaraswamy of Tiptur Taluka, for example, adopts horticultural practices and has a diversified farm with millets and other crops. He says that the problem with inexperienced farmers is that they look for quicker payoffs through the use of chemical fertilizers and stand to lose in the longer term as their farmlands cannot sustain the demands of industrial agriculture.

At a time when we should be reducing “food miles” by eating bio-diverse, local and fresh foods, we choose to adopt monoculture farming practices that ‘promote’ the growth of just certain crops which increasingly deplete the soil of all its nutrients. So, the questions that I pose for myself at this stage is to not just focus on something exclusive such as how best to meet the nutritional needs of my family. Rather, something more inclusive such as, how do I best meet the nutritional needs of my family while making conscious choices to encourage bio-diverse farming, not play a part in farmer suicides, and preserve the health and vitalityof the planet (in that order).

Benefits of bio-diverse farming

Climatologists currently predict that if the trend of the last few decades continues we will see record highs and record lows in temperature in various parts of the world, and each decade will continue to be more extreme in both highs and lows than the decade before it.

A small diversified farm in Pavaguda Taluka has these –Coconut, Areca, Rice, Finger Millet (Ragi), Little Millet (Saamai) and Groundnut. Bio-diverse, local, organic systems produce more food and higher farm incomes while they also reduce risks of crop failure due to climate change. Plus the soil ecosystems are preserved adequately which reduces the dependence on chemical fertilizers to keep spurring the soil on to produce more. Thiscould further increase the reliance of local communities on food sources they know best and that are best suited for the unique requirements of their region.

Chances are that an increase in the adoption of bio-diverse farming, and consequently, a reduction/breakaway from monoculture farming, could play a part in slowing the trend ofclimate change while enhancing the food sovereignty and health of local communities.

Forgotten local foods that are right for us

Until a few years back, when ‘development’ didn’t beckon, millets were deeply ingrained into the culture of our communities. Each region had its own variation of the millet food: Jowar rotis in the Deccan region in South India; Bajra rotis in the west; Sattu in the Himalayan diet; Ragi balls in Karnataka; and Khichdis, porridges of Saamai, Varagu and Thinnai in Tamil Nadu.

Millets which are far more nutritious than rice and wheat use only 200-300 mm water compared to the 2500 mm needed for ‘Green Revolution’ rice farming. In a broad sense, millets are pest-free crops, do not need irrigation for their cultivation and can grow on the ‘poorest’ of soils.

In the hands of traditional farmers, millet farming needs zero energy input. Millet fields are traditionally bio-diverse and therefore sustainable in every way in its true sense, promoting aholistic farming system.

Millets grow with legumes as their companion crops which are one of the finest carbon-fixing tools and therefore a wonderful answer to the climate change crisis.

Millets for food and nutrition security

Forty-four percent of the food grains produced in India are millets , and yet, they are marginalized as cereal crops and ignored completely. The PDS (Public Distribution System) makes food grains available to the poorer sections of the society at a subsidized price. However, the PDS does this only for two grains – rice and Wheat.

The rice and wheat farmers get several advantages in the form of subsidies and a ready market through the PDS. The millet farmers, however, enjoy no support or subsidy for their farming, and in the market, they are sidelined.

Over the last 30 years, millet farming has shrunk by 35%. Without any incentive for growing millets, four million hectares of arable land is being wasted. Millets, if grown in these regions,can feed millions, while also helping India with its food security.

An awesome example of what was achieved since 1996 was demonstrated by the Dalit women of the Deccan Development Society in the Medak district in Andhra Pradesh. They have reclaimed 5000 acres, by growing millets, and have setup a regional distribution system that feeds 50,000 families every year and provides employment to many people.

The PDS, which subjects the poor to a rice diet which is full of carbohydrates, does not offer sufficient nutrition to the poor. On the other hand, millets are storehouses of nutrition and a solution to the problem of malnutrition plaguing the country. Maybe, malnutrition would have never occurred in the first place if India had embraced her local farming practices without giving in to the artificial demands created by industrial agriculture.

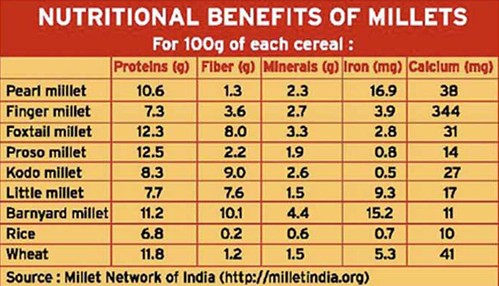

While most of us seek micronutrients such as Carotene in pharmaceutical pills and capsules, millets offer the same in abundant quantities. The much-privileged rice has zero quantityof this micronutrient. The table below shows that by any nutritional parameter, millets are miles ahead of rice and wheat.

Consciously, diversifying the food basket with millets: A step in the right direction for our health as well as the health of the planet

It is no surprise then that a part of the solution (though not the only one) is simply to return to our ‘good old’ foods. The indigenous solution was more millet-based food. I know many ofmy friends who try new fad diets such as quinoa (the grain from South America) and several other lifestyle food choices.

Millet-based foods are not only much cheaper because they are locally produced; they also offer much more variety and very high nutrition. We could all easily contribute to our own health as well as the health of our planet if we just started including millets in our daily diet.

Millet-based foods are not only much cheaper because they are locally produced; they also offer much more variety and very high nutrition. We could all easily contribute to our own health as well as the health of our planet if we just started including millets in our daily diet.All this will take is a little understanding of the grains and your culinary imagination! The nutritional value alone is astounding and could be a big incentive for you to adopt this. Plus, the sheer variety of millets is a big incentive to try and adopt in our daily diets. Of all the millets that I have tried, I like Foxtail (navane) the best to eat with our daily sambar or rasam. I love ragi as a substitute for rice in dosa or idly.

I love Jowar as a substitute for rice again, in Payasam. While just one millet for all foods may not offer a great option, the use of different millets in several dishes offers lots of flexibility, variety and texture, which adds to a certain sense of prosperity and abundance to our palates!

Like in most households, our grandmothers would have more than enough resources to expose us to superb culinary ideas using millets. Some interesting fancy recipes that I have come across based on conversations with my grandmother are – ragi idlys and dosas, amaranth cutlets, arika khichdi, korra dosa, korra bajji, and saama payasam. Here are a couple of websites with great instructions on cooking methods and recipes for millet-basedfoods: www.millets.wordpress.com and www.thealternative.in

An innovative brand such as “Soulfull” strives to provide ragi in a delicious palatable format. They source most of the ragi from an aggregator who in turn collects the grains from 12 to 14 villages around Arasikere in North Karnataka, cleans them and bags them.

It would also be lovely for restaurateurs to help popularize our local cuisines – especially the popular food chains that we keep visiting for that craving of the masala dosa with coffee or the humble idly with the vada as a part of our ‘Sunday Special Treat’. An order of a plate of ragi idlys for breakfast or sattu paratas for dinner when we eat out in many of our local Upaharas would be such a treat for the body, mind, soul and our planet.

Our Role

The problem of climate change can only be examined and addressed in its entirety when we not just embrace the scientific or technical aspects behind it, but rather, our attitude towardsgrowth, our well-being, and a sense of interconnectedness with nature very much like the interconnectedness of the legume and the millet; the bees and pollination, the earthworm and the soil, and our food and our health.

In lieu of all this, most of the suffering is actually imposed on the farmer – the only person who has a relationship with the soil, and who ends up paying a heavy and unjust price for no fault of his.

What can you do immediately? When you spend money, whether a little or a lot, wisely or not, see that you are creating opportunities, supporting local economies, feeding families,lessening poverty, validating life, eradicating fear, inviting magic into your life and lifting humanity higher.

Use less fossil fuels, live responsibly and consciously, grow your own food as much as you can (or encourage it if you can’t), save seeds, and add to the health of the ecosystem. Food is the place that everyone can start making a change by making appropriate choices that are healthier and benefit all concerned – you, the farmer, and the Earth.

Millets show us a way out of our food, nutrition and water crises, and incidentally the effect of all of these on the climate.We must do everything we can to embrace this solution, for our own good and possibly even our very existence!

Arthi can be contacted at arthi.chandrasekar@gmail.com