Source

Social Sector Service Delivery Good Practices Resource Book 2015, NITI Aayog Government of India

Forest Produce Tracking System (FPTS) is a cutting edge web-based application, which was developed and implemented by the Karnataka Forest Department (KFD) in 2011. India’s first end-to-end online system for tracking forest produce, FPTS represents a radical shift in the approach toward transit management as user departments have access to all the data on a single, simplified dashboard which generates reports on transit passes (TPs), rejected applications, check post registers and tracks delayed arrivals too. The FPTS automatically tracks a voluminous number of transactions, handling approximately 4,000–5,000 TPs issued daily.

Rationale

Prior to the introduction of the FPTS, the Karnataka Forest Department (KFD) used a manual system to manage and regulate the extraction of natural resourcessuch as timber, minerals and firewood. A forest officer would inspect a load at the source of release and issue a TP to the owner of the material, certifying the details of the load. This certificate was periodically verified at each forest check post till the sink.

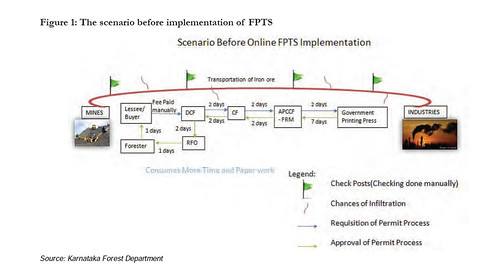

However, this manual system suffered from several shortcomings. It was very time consuming as multiple authorities, approvals and logistics were involved in theissuance of TPs. The enormous volume of paper-based TPs made it difficult for KFD to effectively carry out its core function of monitoring and regulation. Also, the workloadoften forced issuing officers to sign pre-written passes as it was near impossible to be present at all locations to issue loads and transit passes. The absence of a mechanism forindependent verification of TP entries at check posts and the inability to identify the transported material, leading to mixing with illicit material, were among the otherissues that affected the previous system. The system was made even more ineffective by the rampant corruption at the issuing stage, owing to discretionary powers being vested in multiple issuing authorities; printing of counterfeit TPs; ferrying of multiple loads with the same TP; and pilferage of resources as no weight was taken at loading points. Taking mining as an example, Figure 1 shows the operation of the previous manual system ofobtaining permits for the extraction of forest produce and issuing TPs.

The Bellary mining incident of 2009-2010 was seen as a major symptom of this systemic weakness. It generated significant bad press but, on the positive side it created a favourable political climate for reform. The Karnataka Lokayukta report on illegal mining in Bellary had achapter on the use of Information and Communications Technology (ICT) for regulation of ore movement. This provided impetus to the KFD officials in the e-Governanceworking group to take up the task of re-engineering the system. High-level government support as well as very little resistance, owing to the conducive political climate,created favourable conditions for introducing the systemic reform. The FPTS emerged from this reform.

The Bellary mining incident of 2009-2010 was seen as a major symptom of this systemic weakness. It generated significant bad press but, on the positive side it created a favourable political climate for reform. The Karnataka Lokayukta report on illegal mining in Bellary had achapter on the use of Information and Communications Technology (ICT) for regulation of ore movement. This provided impetus to the KFD officials in the e-Governanceworking group to take up the task of re-engineering the system. High-level government support as well as very little resistance, owing to the conducive political climate,created favourable conditions for introducing the systemic reform. The FPTS emerged from this reform.Objectives

The primary objectives of this initiative are to use Information and Communications Technology (ICT) to reengineer the system of TP generation, making it efficient,transparent and simple for all stakeholders. The initiative aims to enable comprehensive and scientific natural resource management by enabling real-time tracking of what is being extracted, from where, by whom and for what purpose, so that policy decisions are based on data, not assumptions.

Key Stakeholders

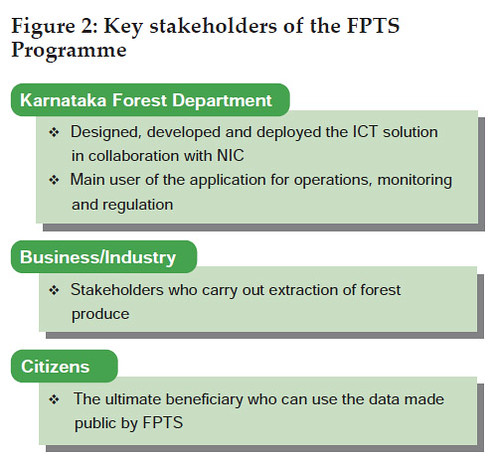

The key stakeholders involved in the programme are KFD, industries and the citizens who ultimately use data made public by this initiative.

Implementation Strategy

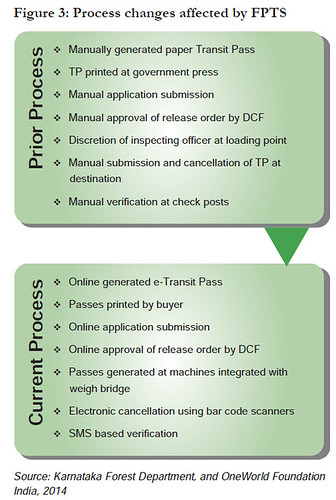

Aiming to establish a self-regulating and persuasive system, the Government of Karnataka began by carrying out end-to-end process re-engineering of the forest produce tracking system, from source to sink. All systemic changes were carried out strictly in conformity with the provisions of the Karnataka Forest Act and related rules so as to avoid recourse to amending existing rules as that would be time consuming. Iron ore was the firstforest produce chosen for tracking (now FPTS also tracks manganese). The process changes were deployed through the web-based FPTS, an end-to-end solutionfor generating TPs and tracking the movement of forest produce from source to sink. Figure 3 presents the process changes affected by FPTS.

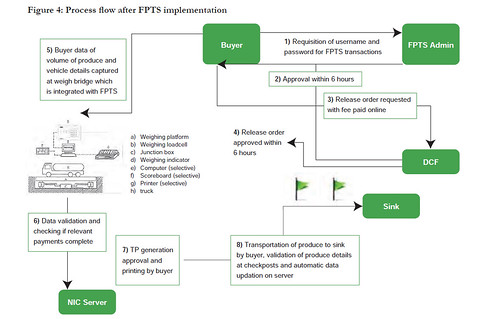

The FPTS application was developed at the ICT Centre of the KFD, with technical assistance from the National Informatics Centre (NIC). The application was developedon .NET and SQL. The entire project, from initiation in June 2011 to state-wide rollout in January 2012, took seven months, with three months spent on application development. The new process is shown in Figure 4.

The FPTS application was developed at the ICT Centre of the KFD, with technical assistance from the National Informatics Centre (NIC). The application was developedon .NET and SQL. The entire project, from initiation in June 2011 to state-wide rollout in January 2012, took seven months, with three months spent on application development. The new process is shown in Figure 4. The implementation of FPTS has enabled a systemic transformation. In the new system, applications are submitted online and buyers can print the release order as well as the TP. The FPTS system prints TPs with quick response (QR) codes and microprint watermarks,which the check-posts automatically verify using 2D QR scanners. The veracity of TPs can also be cross-verified through SMS by messaging KFD INFO (TP No, year) to #09898915455. All basic data on buyers, along with release details, is recorded in the NIC server and used for validation at the weighbridge before generating approval.

The implementation of FPTS has enabled a systemic transformation. In the new system, applications are submitted online and buyers can print the release order as well as the TP. The FPTS system prints TPs with quick response (QR) codes and microprint watermarks,which the check-posts automatically verify using 2D QR scanners. The veracity of TPs can also be cross-verified through SMS by messaging KFD INFO (TP No, year) to #09898915455. All basic data on buyers, along with release details, is recorded in the NIC server and used for validation at the weighbridge before generating approval.Weighbridges are also equipped with digitisers for converting analogue weight to digital and camera integrated licence plate recording to capture vehicle registration numbers. To ensure easy acceptance and implementation of the new system, the offline process was discontinued immediately after the FPTS rollout and only documents generated through FPTS were accepted. The legal status of the e-Transit Pass has faced no problems, as it is in conformity with the Section 4 of the Information Technology Act, 2000.

The new system (FPTS) also provides for a robust system of authorisation. The password policy is strictly enforced. Buyer transactions are facilitated through Secure Word.Digital signature certificates are used to validate the login and authorise transactions and biometric checks are implemented. The overall implementation has become easier as the bulk of infrastructure requirements have shifted to buyers. The new system’s change managementstrategy aims to initially retain the complex functions at the head office and develop simpler functions, and thereafter gradually increase devolution as the acceptance and comfort levels improve.

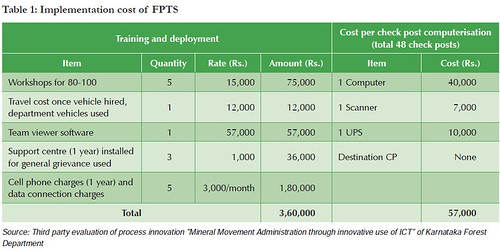

Resources Utilised

FPTS was developed in-house by the KFD and as such did not require any additional resources for web application development. For field deployment, ICT infrastructureand human resource training were the main resources utilised, the details of which are given in Table 1.

Impact

The deployment of FPTS has resulted in transparent, accountable and efficient movement of forest produce from source to sink.

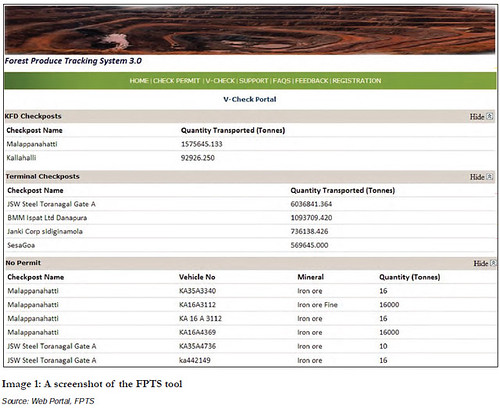

Ease of tracking: User departments have access to all the data on a single, simplified dashboard. They can view reports on TPs (by release order or date). Rejectedapplications, check-post registers and delayed arrivals too can now be tracked using FPTS. The general public can check TP details and track produce movement throughSMS. Every material at the sink can be traced to a source mine even if multiple legs of journey with multiple modes of transport are involved.

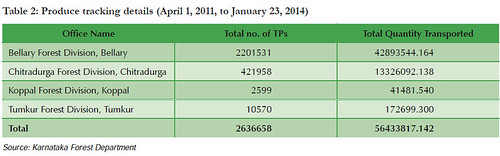

Ease of tracking: User departments have access to all the data on a single, simplified dashboard. They can view reports on TPs (by release order or date). Rejectedapplications, check-post registers and delayed arrivals too can now be tracked using FPTS. The general public can check TP details and track produce movement throughSMS. Every material at the sink can be traced to a source mine even if multiple legs of journey with multiple modes of transport are involved.Improved transparency, better monitoring: FPTS automatically makes the details available at a central location and enables instant report generation, therebygreatly strengthening KFD’s monitoring and evaluation capacity as well as bringing complete transparency to the system. It handles approximately 4,000–5,000 TP issues every day. Table 2 provides details on the total number of TPs generated and quantity transported, tracked through FPTS over a period of three years.

Greater efficiency: FPTS has enhanced efficiency by allowing buyers to enter the TP data themselves. Automation of TP issuance and checking has significantly reduced idle time at loading points. The process time for the approval of a release order has come down to 12 hours, significantly reduced from the earlier minimum time of 21 days. Online generation of compliance and performance reports has eliminated the need for storage space (for paper records) and resulted in environmental gains as well as financial savings. FPTS has computerised a core process, thus providing basic data for a series of other functions such as accounting, offence management, revenue receipts and timber and mineral stock management.

Decline in corrupt practices and increased accountability: Prior to the launch of FPTS, the inefficiencies of the manual system forced even honest businessmen, especially purchasers who had no reason to prefer illegal produce, to indulge in corrupt activities.FPTS eliminated this systemic compulsion, making it easy to do fair business. The system has also enhanced accountability, as the discretion of TP issuing officers at the loading point has been completely removed. The new system undertakes authentication through digitalsignatures, making officers completely accountable. The number of TPs that can be printed is dynamically linked to payments (TP fee and taxes) made by buyers, minimising chances of illegal payments. End users of forest produce can also get details of the produce anddetermine whether it has been sourced legally.

FPTS also enables the use of information by rival social groups (such as competing firms or political parties) to keep watch on each other and thus ensures a strong systemof checks and balances. The elimination of monotonous and repetitive tasks has also resulted in job enrichment for officers, who can now focus on the tasks of regulationand implementation. The overall success of the initiative has renewed faith in ICT solutions among the rank and file of KFD, creating openness and enthusiasm for furtherinnovation and reform.

FPTS also enables the use of information by rival social groups (such as competing firms or political parties) to keep watch on each other and thus ensures a strong systemof checks and balances. The elimination of monotonous and repetitive tasks has also resulted in job enrichment for officers, who can now focus on the tasks of regulationand implementation. The overall success of the initiative has renewed faith in ICT solutions among the rank and file of KFD, creating openness and enthusiasm for furtherinnovation and reform.Key Challenges

Infrastructure gap was the key challenge that the KFD encountered. Besides IT connectivity and infrastructure, awareness levels of functionaries also varied across thestate. This was tackled by prioritising resource allocation for infrastructure development and through training, which were facilitated by high-level support for the project.

The application initially met with lukewarm response from functionaries, as it took away their discretionary powers. This issue was dealt at the highest level through a strategyof ‘indifference and firmness’ till the change was imbibed on a deep and wide scale. Anti-corruption sentiments in the society also seem to have helped diminish potentialResistance.

Replicability and Sustainability

FPTS is a robust application that can handle 10,000 TPs with around 200 concurrent users from 80 mine heads. It can be easily scaled up to handle an even largerworkload. The system can also be easily extended to regulate other forest produce such as firewood, pulp, poles and billets.

As the process is the same in all forest departments across the country, FPTS can be easily replicated with minimum customisation required for master details like administrative structures and names of divisions and functionaries. The system is flexible and can also be modified to handle any new related processes,functionaries and divisions such as the trading of iron ore. It does, however, require a strong IT infrastructure and capacity building drive to be effective.

There is effort toward further enhancing FPTS by adding mining sketches that demarcate and designate the mining area for each buyer. This will increase accountability and enable checks on illegal mining. KFD has developedsome other applications as well, including the following, for natural resource management:

E-timber: Tracks timber movement from source to sink

Huli: Carries out digital census of tigers using PDAs

Bhuvan: Acts as a geo-spatial natural resource database; developed in collaboration with ISRO

Conclusion

The stakeholders involved in the management of forest produce – administrative officials, industry and the general public – now have access to precious real-timedata made available by FPTS. This has made it easier to take policy decisions that are more realistic, sustainable and responsive to the needs of the public and theenvironment. The public has also been empowered to keep a check on malpractices, thereby ensuring much wider accountability.