To understand the grim water crisis we need to look no further than Delhi, where the water table has depleted by 13 metres since 1995 and the scarcity has often sparked off riots between otherwise friendly colonies. Delhi’s water requirement is 3324 million litres per day (MLD). But it gets just about 2634 MLD. The average water consumption is estimated as 240 litres per day; the highest in the country (Halder and Kulshetra 2004)

Even though Delhi’s Chief Minister Sheila Dikshit makes solemn public statements categorically denying that she is about to privatize the ownership, supply and distribution of Delhi’s water. A French Multinational, Onedo Degremont, got the work on one of India’s most ambitious water project. Rs. 200 crorre Water Treatment Plant coming up at Sonia Vihar in North Delhi. There is every indication that this privatization, whether you use World Bank Jargon (Public Private Partnership) or could it be with acronyan like BOT (Build, Operate and Transfer) or O & M (Operation and Maintenance). Degremont has been awarded an O & M contract for duration of 10 years on the completion of the machinery installation process. Mrs. Dikshit justifies this saying “Delhi Jal Board (DJB) will continue to own the water and enjoy full control over its supply. (Halder and Kulshetra 2004)

The most curious aspect about the contract is the counter guarantee clause. There are provisions in the contract, which assure Degremont payment even in the event of the Sonia Vihar lying idle. The matter assumes significance against some Third World ground realities. Multinationals doubt the ability of the poor consumers to meet their bills and extract promises of governments meeting the shortfall in revenue. No multinational would be willing to invest in the Third World water markets without counter guarantee to cover the risk (Halder and Kulshetra 2004)

Public-Private Partnership is a dangerous concept of the World Bank. South Asia receives 20% of the World Bank’s water loans. As per various reports of the World Bank, by 2025, two thirds of the world population will suffer from drinking water shortage. Economic theory says that less availability with more demands ensures the highest profit. So water trade can be termed as oil of the 21st century.

Private water companies have failed to provide guaranteed quality water even though people continue to pay high prices. In the Indian conditions, Delhites will be compelled to pay a monthly bill of Rs. 2000 instead of the present bill of Rs. 50. An additional tax on the sewage will also be charged which means; Delhites will have to pay Rs. 2,500 per month (Mohanty 2004)

Water privatization generates unemployment. In England, 10,000 employees were compelled to sit at home after privatization and in Philippines 40% employees were forced to leave the job. Experience shows that once water resources are privatized, the government hardly gets them back (Mohanty 2004)

Resident’s thirst for adequate water supply is far from being quenched, scenario is worst in South Delhi. According to one resident in Saket, it is shame that even after 57 years of the country’s independence, the government has not been able to fulfill one of our most fundamental requirements. At times, we have to contend ourselves with just half a bucket of water to finish our daily chores. Another resident in the same locality wakes up at about 2.30 a.m at night and with a torch in his hand does not go back to bed until he is seen that much sought after trickle (Times of India, 2004 a.)

Residents of Siddharth Extension in South Delhi have not got any water for the past two days. In east Delhi’s Laxmi Nagar the situation is almost same. In Dwarka many people use bottled water to wash utensils (Sinha a. 2004)

While water wars are predicted in the next few decades, the city’s inequitable supply – that ranges from 400 litres per person daily (LPCD) in NDMC and Cantonment areas to 30 LPCD in far flung south Delhi areas, may soon lead to a law and order situation (Sinha b. 2004)

The worst news is that things are not likely to change much till 2015 for revamping the city’s distribution network, which means different section in Vasant Kunj will keep getting water between few minutes and two hours, while Civil Lines will retain its four hour supply. Similarly, the city’s VVIP can continue washing their cars and garages as they enjoy the highest supply of in NDMC areas. (Sinha b. 2004)

Eighty per cent of Delhi’s ground water is in extremely worrying categories of over exploited and dark; with drawl is well beyond what is recharged (Mago 2004)

In peak summer at an estimate about 15 million people in Delhi are facing crippling water shortage, and are looking for any one who can provide them even one bucket of water. In many localities, people are using treated water to take bath, which is used for gardening. People have to decide each day, what is their priority - desperation has driven some people to the unusual step of stocking mineral water not only for drinking, but also for taking bath (Pioneer 2004)

With water situation worsening by the day, Delhi Police have stepped its preparedness for the after affects of acute water shortage. Police have identified over 35 potential ‘trouble areas’. These flash points include up-market areas like Defence Colony, Vasant Kunj, Greater Kailsah and middle class localities like Patel Nagar, Malviya Nagar, Dwarka, Kalkaji, Tilak Nagar, Vikas Puri and Shahpurjat. As well as lower income group localities like Sangam Vihar, Narela, Najafgarh, Uttam Nagar and Dabri. To diffuse any potential situation the local police have been asked to liaise with the Resident Welfare Association (RWAs). District control rooms of the troubled areas too have been alerted to watch out signs of trouble. South district, which has the maximum number of trouble spots, stepped up beat patrolling in the identified areas. (Gulia 2004)

It is unfortunate that NDMC covers only about 2% of the city gets 30% of the water supply. It is very unfair distribution. A little water can be diverted to trouble areas to ease the situation.

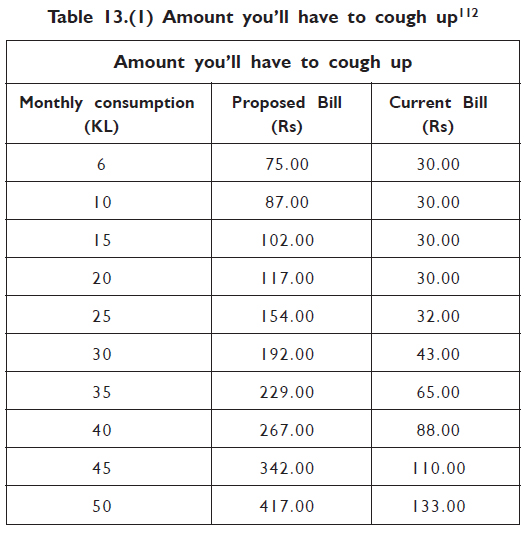

Water tariff is set of soar in the capital to almost double the existing rates. The existing rate for 20 kilolitre of water is Rs 30 while the revised rate for the same quantity of potable water would be Rs 117. Similarly 30 kilolitre of water will be priced at Rs 192 as against the present slab of Rs 43, while 40 and 50 kilolitre of water will be available at Rs 267 and Rs 417 respectively. The impact of the tariff restructuring on the domestic bills will be felt most in the consumplry levels which exceed 25 kilolitres (Jha 2004).

Three categories of Consumers: -

CATEGORY I : Domestic consumers, ranging from pure residential premises to bulk connections for JJ colonies, orphanages and religious premises. (Total consumers : 13,89,273)

CATEGORY II : Non-domestic consumers, including commercial establishment like shops, offices, household industries, restaurants, public urinals, bank and professional training institutes. (Total number of consumers : 91,596) (Jha 2004)

(Jha 2004)

CATEGORY III : Commercial premises having large water consumption, like cinema halls, ice factories, private educational institutions, industrial units, photo labs, horticulture farms, power plants, hotels, banquet halls ( Total number of consumers : 21,075)

Working out the Bill

The new tariff may be calculated like this: B=F+1.5 X I X U

B is the water bill amount in rupees

F is the fixed charge. In domestic category, it may very from Rs. 40 for LIG flats to Rs. 100 for houses built in 100 – 150 sq.m plots and Rs. 150 for bungalows.

Commercial and industrial rates may be between Rs. 250 and Rs. 600.

I is the incremental factor or rate per kilolitre. It may be zero for those consuming up to 6 kilolitres. Then from 6-20, 20-40 and above 40 KL, it could be 2.5 and 10.

U is number of units consumed in kilolitres.

The new tariff would have two parts. There will be a fixed charge that will vary depending on the size of the place where the connection is provided. Then there would be a slab-wise charge for using water. There may be a 50 percent surcharge on the consumption charge for sewerage collection and treatment. (Sinha 2004 c)

Suez-Degremont Water Plant at Sonia Vihar

This is the first contract of this size after Bombay for Degremont. Suez-Degremont has been awarded a Rs. Two billion contract for the design, building and operation of a 635 million litres/ day at Sonia Vihar. The contract is initially for 10 years. The profit of Sonia Vihar plant is guaranteed by the government during the period of 10 years.

Construction of the giant 3.25 meter-diameter pipe on a stretch of 30 kilometres from Muradnagar to Sonia Vihar is going on, and till date about 10 kilometres of the pipeline has been laid down.

The disastrous impact of this project on the farmers of Western UP is evident from the fact that this area is totally dependent upon the canal for irrigation. Even before being operationalised to divert 630 million litres of water/day from irrigation, farmers are feeling the impact of corporate greed for profit. The Upper Ganga Canal is being lined to prevent seepage into the neighbouring fields (an important source of moisture for farming) and recharge of groundwater, and farmers are being prevented from digging wells even as they are reeling under severe drought.

The lining of the canal to prevent recharging of groundwater has terrified the farmers of the whole region of Western UP. At a meeting organized by Navdanya on 21 July at Chhaprauli, the land of Chaudhary Charan Singh, ex-Prime Minister, farmers stated, “we will not allow the Canal to be lined and supply water to Delhi. Instead the government should link the Upper Ganga Canal to the Yamuna Canal through this area to tackle the severe drought.”

In an interview to a national magazine, a senior manager with Degremont said, “right now, we are happy with a profit of Rs. 10 crores per annum. Other companies may be content with managing and operating existing plants owned by individual civic bodies. But we don’t want to dabble in that. We have very strict quality control and would like to maintain our image as quality providers to our clients”

The water scenario is worst in Delhi slums, for example Sanjay colony slum of New Delhi has population about 15,000 – 20,000 with about 4500 households in the locality. Majority of the population is self-employed and are engaged in making dari, mate and other clothes for sale.

In this area people collect water from different sources depending on the availability such as DJB tanker, MCD pipe water supply and from Sulabh International. DJB tanker comes daily but it has no fix time for water distribution. The water that comes from MCD pipe water has fix time for water supply but it only comes for 1-2 hr in the evening (around 4.30 p.m.). At MCD pipe line people made bore and fetch water from it. If the people don’t get water from the above sources they are forced to get it from Sulabh International near Kalka ji temple for which they have pay @ Rs. 2 for 20 liter or so.

It is found that if women were not able to collect, from these sources 60% of them buy water from Sulabh international 40% also pay rickshaw charges.

Seventy per cent of the women said that water comes from different source is clean but 30% said that water sometimes come clean sometime not. People said that DJB water come clean but whenever tanker comes they put their pipe in tanker itself that makes water unfit for consumption.

On total time consumed for water collection 60% of women said that they have to spend 2-3 hr/day and 40% spend more than 3hr, sometime they have to wait for full day. Fifty per cent travel for 1 hr. 20% for 1/2hr. and 30% for 10 minutes to collect water.

On water consumption 50% family use 100 lit of water /day, 30% use more than 100 lit./ day and 10% use 60 lit of water daily.

Almost all the women said their household job suffer in collecting water as well as children get neglected during water collection. About 80% women store water in container for next day because it's not certain that water will come on next day. A large number of people in the locality suffer from waterborne diseases such as malaria, jaundice etc. Only 10% women use chlorine tablet to purify the water.

In Jeevan Jyoti Rajiv Camp slum locality, people collect water from different sources viz. tube well, DJB tanker and Sulabh International. MCD water pipeline though meant for industrial supply but due to non-availability of water people are forced to fetch water from this pipeline.

The water from MCD pipe though has fix time but it is supplied for -2 hr in the evening. At pipeline some innovative people made bore and fetch water from hand pump. If they fail to get water from these sources, they get it from Sulabh International near Kalkaji temple for which they have to pay @ Rs. 2 for 20 liter.

Half of the women have to spend 1 ½ - 3hr, 40% ½ - 1 hr and 20% for more than 3 hr per day to collect water. The distance travel by 80% women is 10-15 minutes and 20% take ½ hr. On water consumption 40% said that they use 100lit/day,10% said 80 litre, 30% use 60 litre/day and 20% use more than 100 litre/day.

For Eighty per cent of the women household job suffer in collecting water. All the women store water in container. Regarding the cleaning of water 80% strain water by cloth and 20% use chlorine tablet. Twenty per cent people in the area suffer from fever and diarrhoea.

Alternative for Quenching Delhi’s Thirst

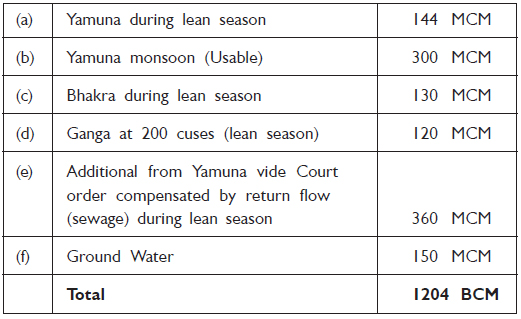

Sureshwar D. Sinha (2003) has suggested the ways to rejuvenating the Yamuna and reviving local water bodies, which would meet the water demand for Delhi.

At present the following sources are available for supplying water to Delhi for horticulture land domestic use. Taking each of the above-mentioned ‘Principles of Good Water Management’ in turn, let us look at the measures that could ameliorate the deteriorating ecosystems around Delhi and provide its dwellers with adequate supplies of water.

Taking each of the above-mentioned ‘Principles of Good Water Management’ in turn, let us look at the measures that could ameliorate the deteriorating ecosystems around Delhi and provide its dwellers with adequate supplies of water.

The Yamuna has no flows between the barrage at Tajewala and Delhi’s northern border, whilst waters allocated to this state from the Yamuna, as well the 0.2 MAF (Million Acre Feet) allocated from the Bhakra system, are conveyed to Delhi through canals. If Delhi’s allocation of waters from the above systems are allowed to flow through the river, the wastage would be 25% less, and the river would recharge ground water en-route, and keep itself clean, with substantial flows, as follows: -

a) Exchange of Delhi’s Bhakra and Haryana’s Yamuna Allocations. If the allocation to Delhi from Bhakra system is exchanged with Haryana’s equivalent amount allocation from the Yamuna, the same would envisage a release of 371 cubic feet per second (cusecs) at Tajewala.

(b) Delhi’s own allocation be allowed to flow down the river instead of through canals, the average additional flow in the river would be 242 cusecs.

(c) The allocation in the inter-state agreement ‘for ecological reason”, gives us an additional flow of 570 cusecs.

(d) The allocations for lower area canals, is about 800 cusecs.

Adding all the above flows, we would have a flow of 1983 cusecs or nearly two thousand cusecs, during the lean seasons. This would not only revive the river, it would have a salutary effect on the recharge and cleanliness of the groundwater of the basin, including that of Delhi.

For storing monsoon waters of supplies to cities of the Yamuna basin in and around the state of Delhi, following measures are suggested.

(a) Creation of Five Flood Plain Reservoirs within Delhi, four of which could be quite large and one would be the expansion of an existing small lake. In addition every effort must be make to fill the old tanks, ‘jheels’ and ‘hauzes’ of this ancient city with clean monsoon waters.

(b) Rain Water Harvesting Apart from harnessing the flood waters of the Yamuna and Sahibi, as well as the Ganga as mentioned above, there is very good potential for rain water harvesting at the state colonies, and individual level. Delhi has an area of some 1485 sq. kms and average rainfall of 61 cms. Then the total precipitation is of the order of 906 MCM of water. At present most of these waters join the flood spills of the Yamuna, or are absorbed by plants and at upper soil levels.

The revival would greatly enhance natural groundwater recharge, improve the ecology and the bio-diversity of the areas drained by them and their surface flows could also be utilized if supplies became deficient.

High density of population has compelled most modern metropolis’ to treat their sewage up to the tertiary stage, converting it to bathing quality water, and then to further treat these supplies as water for domestic use.

The alternatives suggested above are also those that would cost less and consequently would be a lesser drain on the exchequer due to the corrupt practices encountered in the execution of water projects.